Dust, Dirt and Danger

An Article published first in Popular Photography 1995

Trails of grey dust linger like a thick blanket over thousands of pilgrims making their way through the desolate sea of sand surrounding Mt. Bromo. The narrow steps leading to the rim of the volcano are choked with worshippers carrying food and livestock to the summit. Herded in like an animal in a flock I am forced to move slowly towards the crater rim. Clutching my tripod with my left hand while covering my mouth and nose with a thick shawl, I'm gasping for air. It's not the volcanic ashes that irritate my lungs, it's the white pungent sulphur mist rolling down the cone-shaped walls of Mount Bromo.

It is almost 2 am when the full moon breaks through the clouds and reveals the whole scale of the mass exodus. There must be over two thousand pilgrims patiently moving up the steps and equal numbers returning down empty-handed. I hate crowds but for this special night I'm determined to put up with them. Tens of thousands of Tenggerese, who live on this rugged mountain plateau in East Java, have gathered to worship and celebrate the god of their sacred volcano during the special night of Kasada.

Circle of Pickpockets

At last I've reached the top of the stairs and I push and squeeze through the thick barrier of bodies blocking the access to the rim. Jammed in by the crowd, unable to move, I suddenly realise that I am being pickpocketed from all sides. There are hands everywhere, pulling on my tripod, jerking my backpack and pushing their way into my pockets. Powerless to escape I elbow and jostle, then desperately kick and scream. A few moments later I break through the tight circle of pickpockets. Furious and out of breath I check the zippers of my backpack. The two heavy duty safety pins are still in place holding the two zippers together. The outer pocket of my camera jacket has been tampered with but besides a small knife, a lens cap and some rolls of fresh film, my losses are light. I am relieved that nobody managed to lay their hands on my already exposed films. While going through my pockets I am approached by some young Danes. "How much did you lose?" "Well, I'm lucky, it could have been worse. How did you go?" I inquire. The group of Danish backpackers didn't fare too badly either but some of their British friends lost money-belts, wallets and a couple of cameras.

When checking the time I realise that my watch is hanging loose on my wrist, perhaps another failed attempt by a pickpocket. I brush clouds of dust from my arms and unzip my camera jacket to remove the large clear plastic bag which has protected my F4 and flash from the abrasive volcanic dust. I extend the feet of my tripod and get ready for the first light in the sky.

Origins

Over the years Indonesia's Mount Bromo has attracted hundreds of thousands of photographers although very few of them have experienced the special night of Kasada, sharing the narrow space of the crater rim with more than 5000 worshippers. According to legend, the origin of the Kasada ceremony goes back nearly a thousand years to the reign of King Brawijaya during the Majapahit era. A childless royal couple who once ruled the region climbed to the top of the holy Bromo volcano where they beseeched their God to grant them children. The God agreed on condition that they would sacrifice their last child into the Bromo crater. Years later they, finally, reluctantly kept their part of the bargain and since that time the Tenggerese people arrange an annual ceremony, bringing offerings from their crops and cattle, on the 14th day of the full moon in the month of Kasada.

All night the Tenggerese have been throwing offerings into smouldering Mount Bromo. But before the gifts for the gods can fall into the glowing depths of the volcano they are intercepted by an army of poor peasants. Clinging to narrow ledges and carved-out shallow footholds, dozens of desperate men try to catch the offerings being hurled into the crater. The rewards for risking their lives are generous as poultry, food, money and cigarettes shower into the fiery furnace, most of them skilfully caught by the villagers.

First light

The soft colour change in the sky is signalling the approaching sunrise. I compose my first shot on my F3 with a 20mm lens, a view of the rim with the congregation silhouetted against the glowing core of the volcano. With the 80-200mm lens on my F4 and the SB24 set to rear sync I zoom into some of the worshippers throwing their offerings into the smoking interior. As the sky turns pink I spot a rugged tribesman ready to throw his live chicken into the crater. I lean forward, dangerously close to the slippery rim, to gain a better composition and just as he hurls his chicken I press the shutter. Buzz, click, damn it, I'm out of film.

Changing film

It happens to all of us - the film always runs out at the worst possible moment. Just when you have lined up your subject matter and press the shutter your camera strikes and will not advance beyond frame 37. It never seems to happen when you have plenty of time but always when your elusive subject is in perfect position. Although re-winding and loading film may only be a 10-second flat interruption you may still miss your shot. And no matter how fast you change your film, some dust will always settle on the open back of your camera. Abrasive volcanic grit can scratch the unwinding or rewinding film and destroy that once in a lifetime image. However, by holding the camera body upright I can remove the exposed film and load a new roll with much reduced risk of dust creeping inside the camera.

My Moment in Time

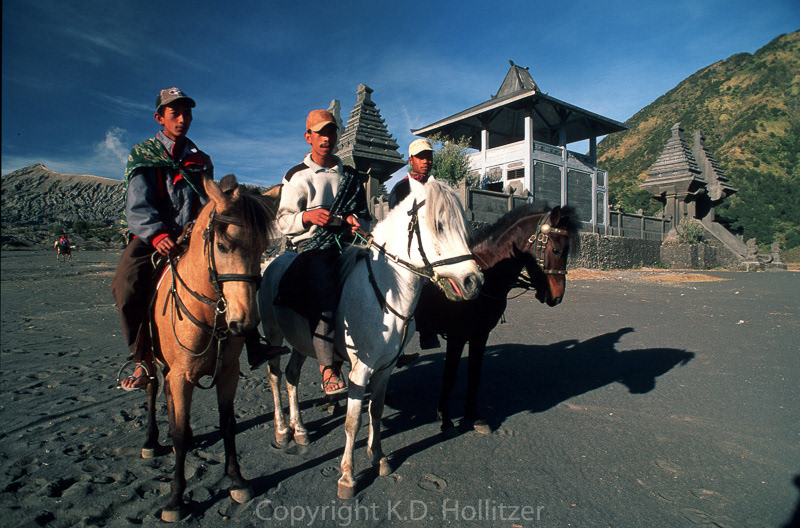

As the sun rolls over the horizon hundreds of camera flashes go off to capture the enchanting moment. For myself the magic spell of Kasada is broken and I focus my lens on the endless exodus spilling down the dusty path into the black sea of sand. As the sun slowly disappears behind a solid wall of cloud and the light turns flat, I'm not even upset. Three days of exhausting shooting in varied light conditions, starting with the preparation of the Kasada festival and its associated events to the final night of mass worship on the crater rim, should have yielded sufficient pictures to illustrate half a dozen articles. Just as I pack all my cameras to descend from the crater rim, my moment in time has arrived. For a few seconds the morning sun breaks through the clouds, illuminating the narrow path of the returning horsemen. I managed to take just one picture, which has proved to be my shot of a lifetime, winning countless awards, appearing on centerfolds and front covers and ultimately being utilised by the Nikon Corporation, Japan in a worldwide advertising campaign.

Shooting stock and freelancing for magazines is hard work but it can be rewarding for the dedicated photographer. Often you have to put up with heat, dust, dirt and pickpockets to get that once in a lifetime shot. You drag your camera gear through the country in rusty utes, jeeps, light planes, on horseback and in open canoes. Most of the time, however, you lug all your photographic equipment yourself on your sore back. And as there is no substitute for a steady tripod the 4-kilo Manfrotto is one of the heavy-weights you can't be without.

Camera survival

I am convinced that without my daily cleaning ritual all my SLR's would have stopped functioning long ago. Whenever I have spare time and sufficient light I dust off my camera equipment. In the daytime I find myself a table near the window or at night the best lit table in the restaurant and remove the excess dust from the camera bodies. Using a strong puffer and a soft cosmetic brush any dust is easily removed from the filters covering the front lens elements. But even more important is to remove every single grain of dust that may have settled on the unprotected rear element of your lens. Any dirt on the rear element will show up clearly in your pictures. It is pointless to clean the dust clinging to the mirror as it won't affect the picture quality. Stubborn dirt and greasy fingermarks on the camera body can be removed with a soft cloth soaked in a mixture of methylated spirits and distilled water which I carry in a small plastic bottle. I also regularly wipe the viewfinder and the electrical contacts on auto-focus lenses and bodies with the same cloth.

Camera safety

As a photographer you can never relax, you're constantly looking for subject matter while keeping a sharp eye on your camera equipment. There is never a leisurely stroll to the bar without lugging your camera bag along. Even at breakfast it is wise to keep your gear with you. The most likely place to lose your equipment is from your hotel room. And even if you are fully insured you can seldom replace your equipment on location.

Film safety

What is even more important to me than all my photographic equipment is my exposed film. Double-locked in a hard-shell suitcase, all my rolls lie numbered, waiting for development on my return. Depending on the hotel security, or lack of it, I have, in a fit of mistrust, even chained the entire suitcase to the metal downpipe to slow down potential robbers. Fresh film I always like to store in the bar refrigerator in my room, especially when shooting for longer periods in the tropics. I hand-carry every single roll in a clear plastic bag through airport security; my film never travels unaccompanied in the suitcase. Over the years I've lost two suitcases but never any films.

Two hours after the unforgettable sunrise I meet Mike, a veteran Australian freelance cameraman, in the Bromo Permai restaurant, as he cautiously inspects his vegetable chap chay so as not to swallow any of the well-cooked flies. Dirty and exhausted after two sleepless nights his boyish smile has turned sour. "How is it going Mike?" I ask him. His face turns to a wry grin. "They got my 16-1 Canon zoom from the bumbag and I didn't even notice." While Mike was shooting with his Betacam the packed crowds of pilgrims spilling on to the rim, some talented pickpockets managed to steal his $5000 TV zoom lens. Needless to say, Mike wasn't insured, just like myself and most other freelancers, who can't afford to pay the high insurance premiums. Dust and dirt may be the biggest enemy to your precious camera gear but common theft constitutes the greatest danger.

the end

The Hollitzers are Sydney-based photojournalists and have been published in Asia, Australia, US and Europe.